Eagle-faced Army officer Robert Carter dedicated an American Indian Wars memoir to his commander Ranald Mackenzie, a fellow Civil War Vet who fended off Confederates attacking Washington D.C. in July 1864, helping save the nation’s capital at 23 years old.

Still soldiers as young men 10 years later in the Southwest, Capt. Carter credited Gen. Mackenzie’s command for doing “so much to make civilization possible on the borders of far Western Texas.”(1) At The Battle of Palo Duro Canyon, September 28, 1874, Mackenzie’s 4th U.S. Cavalry soundly defeated a larger force of Kiowa, Comanche, and Cheyenne warriors, opening the Southern Plains to white settlement.

The Red River War battle resulted when the Federal Government ordered all Southern Plains Indians to return to their reservation agencies by August 1, 1874.(2) 400 Federal cavalry successfully forced the holdout tribes onto reservations in a series of raids between June 1874-spring 1875, ending American Indian life in the canyons of West Texas.(3)

10 years after Capt. Carter and Gen. Mackenzie fought in the U.S. Army under the banner of emancipation, the soldiers of that same Federal Government completed a campaign Carter predicted would be one of “either driving these hostile Indians into their reservations or one of subjugation and annihilation.”(4)

| Fighting Force | Commander(s) | Size |

| Cheyenne | Stone Calf, White Shield | 1500 across 3 tribes |

| Comanche | Mowway, Quanah, Isatai | |

| Kiowa | Lone Wolf (Guipago) | |

| 4th US Cav Southern Column | Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie | 400 men in 8 companies |

Holdout Tribes Strategy

Preferring the mesquite roots and ample game of Palo Duro Canyon over the thin soil and arid reservation region in Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma), bands of Southern Plains Indians attacked bison hunters and American travelers throughout summer 1874. “Determined to keep whites from their favorite hunting grounds”(5) the tribes angered the Bureau of Indian Affairs enough that the agency granted the Army permission to pursue Indians onto reservations.(6)

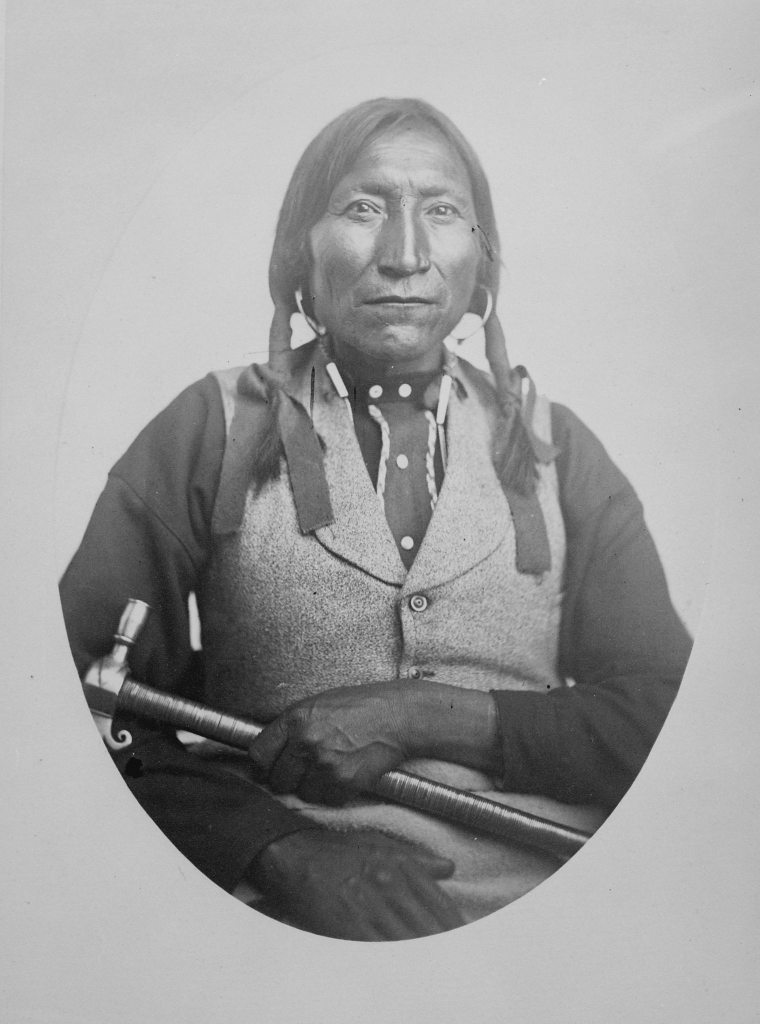

The holdout tribes sought to use defensive advantages offered by the 800-foot deep “Grand Canyon of Texas”(7) that now constitutes a sprawling state park 25 miles southeast of Amarillo. In 1874 there was a single route in and out of the canyon. The warriors hoped to lure Federal cavalry into a trap by concealing themselves behind rocks looming 800 feet above the canyon, then cut off a U.S. retreat. Though inferior in firepower to the Federals, the warriors were equipped with pistols and rifled muskets. Various leaders held command in the inter-tribal force but American primary documents most mention Lone Wolf. The sinewy 54 year-old Kiowa chief was a longtime Federal foe who could not be given any slack according to noted Indian fighter Phil Sheridan.

United States of America Strategy

A multiracial force of Black Seminole scouts, Tonkawa guides, and 400 cavalrymen of the 4th U.S. blitzed across the Texas panhandle in late summer 1874, fighting 14 engagements between August and November.(8) Aggressively using their permission from the Federal Government to pursue holdout tribes, the cavalrymen armed with Winchester repeating rifles embarked on a war of attrition. The Federals hoped to surprise warriors camping in villages along the Red River in Palo Duro Canyon, raid and destroy their camps, then beat a hasty retreat out of the canyon.

The Battle

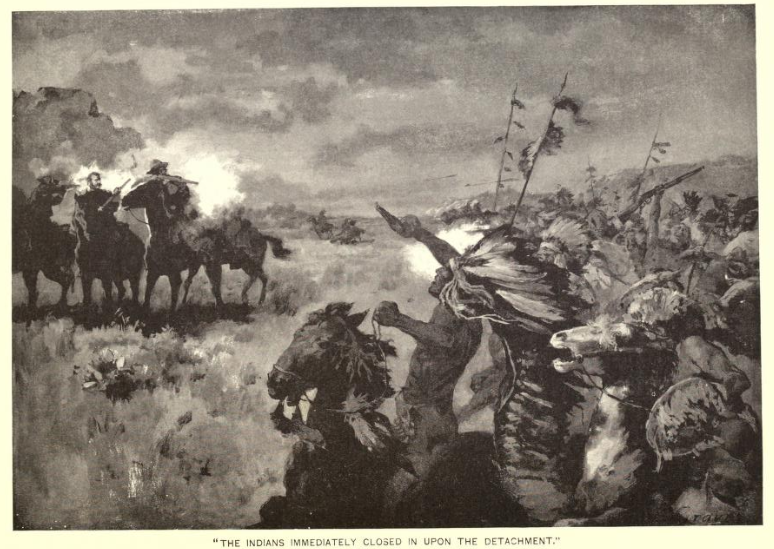

At 4:00 AM, September 28, 1874, Tonkawa scouts uncovered a fresh trail to Palo Duro Canyon, and the 4th U.S. began advancing from the southeast after skirmishing with a vanguard of holdouts at Tule Canyon. Federal cavalry completed a single file descent down a narrow zigzag path into the canyon. Their use of this path previously occupied by buffaloes and ponies surprised the holdouts, setting the warriors in flight shortly after sunrise.

4th U.S. Cavalry Company H, the raiding party, formed in line in the abandoned Indian camps and took inventory of their stock of 1,400 captured ponies. The company was soon fired upon by warriors using boulders as breastworks high above U.S. forces in the canyon. The Kiowa’s small arms fire briefly forced the Federals to fall back from their only exit out of the canyon around 12:00 PM.

Around noon Gen. Mackenzie reported a movement of warriors attempting to block this exit. In a race to safety, Mackenzie’s 4th U.S., who covered 60 miles a day on campaign, reached the finish line first. Finding no warriors blocking their way, Cos. D, I, and K returned to the abandoned camps and traded small arms fire with scattered bands of warriors. The desultory fire had little effect, as the 4th U.S. suffered a single casualty compared to the warriors’ 60 killed. Accepting their grim situation, the Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowas left Palo Duro Canyon for good between 3:00-4:00 PM.(9)

Without horses and supplies, the Southern Plains Indians who had been in the canyon had little chance to escape the cold of the coming winter.(10) The Federals were content to let the warriors slip away since the cavalry regiment had accomplished their goal of forcing the holdout tribes off non-reservation land.

Aftermath

After marching overnight, the cavalrymen reached a Federal wagon supply train near Tule Canyon 70 miles southeast. The following morning, September 29, U.S. forces ate their first meal in two days then rounded up thousands of captured ponies into a canyon and shot them. Capt. Carter said “it seemed a pity…but there was no other alternative. It was the surest method of crippling the Indians and compelling them to…stay upon their reservations which they had fled from. Many were the best race ponies they had and many pesos had been waged upon them.”(11)

Gradually each holdout tribe accepted reservation life in Indian Territory. In February 1875, Lone Wolf led Kiowas to their reservation, was found guilty of rebellion, and sentenced to confinement in a military prison off the coast of Florida. A month later 1,600 Cheyennes reported back to their BIA agency. The last domino of American Indian life in West Texas fell in June 1875 when the final 400 holdouts returned to Fort Sill in modern Lawton, OK with 2,000+ horses.(12) According to military historians, in the end, “exhaustion, not defeat in battle, forced the tribes to accept reservation life.”(13)

Works Cited

Beyer, W. F. & Keydel, O. F. (1906). Deeds of Valor, Vol. 2. Detroit: Perrien-Keydel Company.

Bradford, J. C. (2003). Atlas of American Military History. Palgrave Macmillan.

Carlton, P. H. (2003). The Buffalo Soldier Tragedy of 1877. Texas A&M University Press

Carter, R. G. (1935). On the Border with Mackenzie, or, Winning West Texas. Pickle Partners Publishing.

Hinckley, J. (2022) The Backroads of Route 66: Your Guide to Adventures and Scenic Detours. Motorbooks Publishing.

Endnotes

- Carter, 1935, p. 3

- Carlton, 2003, p. 43

- Hinckley, 2022, p. 103

- Carter, 1935, p. 755

- Carlton, 2003, p. 42

- Ibid, p. 43

- Hinckley, 2022, p. 102

- Carlton, 2003, p. 43

- Preceding 3 paragraphs summary of Carter, 1935, p. 779-788

- Carlton, 2003, p. 43

- Carter, 1935, p. 789

- Carlton, 2003, p. 43

- Bradford, 2003, p. 96