Benedict Arnold’s Colonials captured an entire British army at Saratoga in Oct 1777, convincing France to militarily support the American cause. On Sep 6, 1781 the ex-Patriot officer Arnold, who four years earlier delivered the turning point of the Revolutionary War, overwhelmed his former counterparts in Connecticut. The final Redcoat victory of the war featured a Black Patriot bludgeoning a British officer to death, American wounded left baking in the sun, and resulted in a new nickname given by local residents: Traitor Arnold’s Murdering Corps.

When Continental Commander George Washington reprimanded Arnold after a court-martial in Dec 1779, the cranky Connecticut-born officer decided to give away West Point. Washington and his staff discovered the plot the following April, the Commander in Chief lamenting, “Arnold has betrayed me. Whom can we trust now?” Arnold received 6,000 pounds, a lifetime pension for his children, and the lasting enmity of Redcoats who blamed him for the death of their friend John Andre, executed for his involvement in Arnold’s plot. In Norwich, an American mob destroyed the gravestones of Arnold’s father and infant brother.(1)

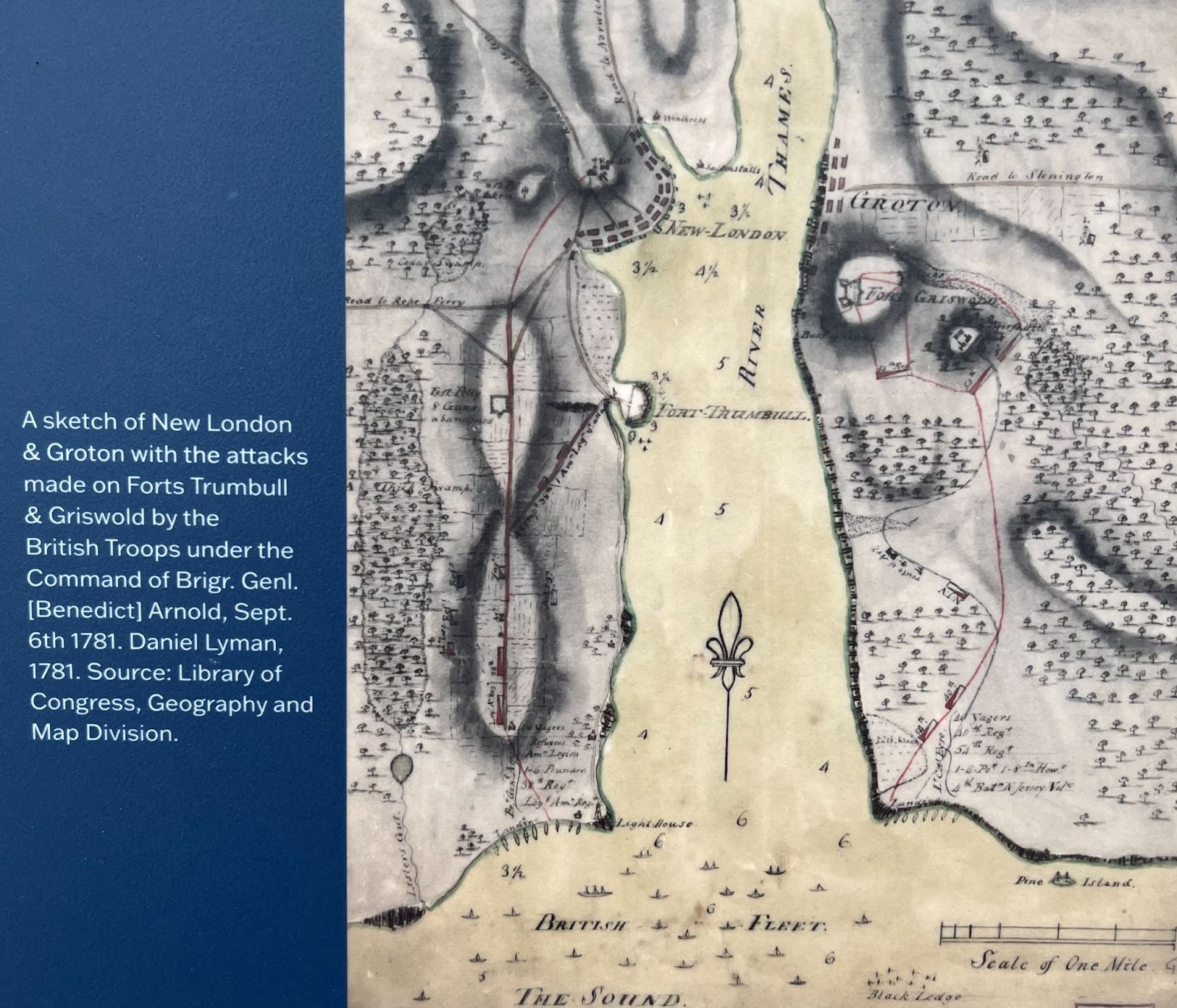

After a middling campaign commanding British operations in Richmond that mostly involved burning tobacco warehouses, the-hated Brig. Gen. Arnold struggled to secure a meaningful command. With the meaningful theaters of war in New York and South Carolina by Sep 1781, British Gen. Henry Clinton dumped Arnold in the mouth of the Thames River outside New London. The Connecticut seaport provided safe harbor for American privateers who captured British merchant ships.(2)

Arnold’s fleet of 1700 landed on both sides of New London harbor the morning of Sep 6, splitting into columns. One quickly took Fort Trumbull at New London and another Fort Griswold at Groton after heavy resistance from 178 local militia. In the latter fight, militia claimed British forces bayoneted wounded Americans. Official records disagree, but both sides agree that Colonial wounded were left outside the fort in the sun while Redcoats were buried in the shade of parapets.

While Arnold’s column at New London set fire to the town’s ships and warehouses, British Col. Edmund Eyre’s column was driven back twice at Fort Griswold by Col. William Ledyard’s determined militia. In their third assault, Eyre’s Brits scaled ladders entering the fort and overwhelmed its defenders with 16-foot pikes used to board naval vessels in close combat.(3) Ex-slave Jordan Freeman speared British Maj. William Montgomery to death as an American prize, but the Colonials lost 145 killed and wounded (81.5% casualty rate). Freeman was himself afterwards killed by a bayonet thrust.(4)

Some Colonial narratives account for the lopsided casualty total with claims of a general massacre by the British. However, American Veteran Thomas Hertell’s account of 70 “badly wounded..Americans collected and laid side by side on their backs and brutally bayoneted” also includes this 1832 footnote: This account of Hertell contains many statements that are not in agreement with other accounts, but it serves to show the town talk of the time, and its recollections by him fifty-one years later.(5)

A reliable Colonial account, including correct details about American casualties being laid out on the sunny parade ground while the British were buried in shade outside the fort, does agree with one example of British atrocities. Wounded Americans were loaded into a wagon by a bumbling British burial party who then launched them down the hill from Fort Griswold. After coming into contact with an apple tree, the wagon ejected tens of Colonial militia, killing them from the shock.(6)

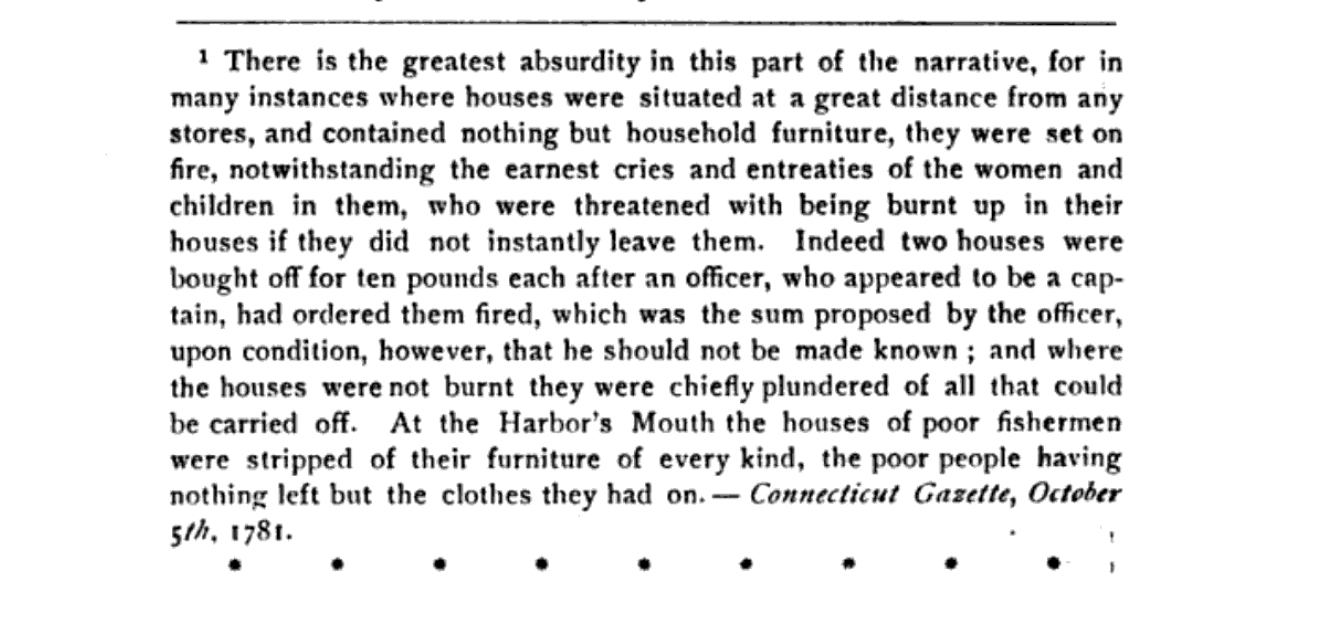

Benedict Arnold spent the evening dining at the house of a Loyalist friend in New London before his meal was interrupted by undisciplined British soldiers who burned the home after misinterpreting orders.(7) Though Arnold claimed in his after action report that British forces made every effort to prevent the “unfortunately destroyed” town from burning, the Connecticut Gazette reported that Arnold’s men rioted until residents had nothing but the clothes they were wearing.

Works Cited

Harris, William W. The Battle of Groton Heights: A Collection of Narratives, Official Reports, Records, Etc., of the Storming of Fort Griswold, the Massacre of Its Garrison, and the Burning of New London by British Troops Under the Command of Brig.-Gen. Benedict Arnold, on the Sixth of September, 1781.

- Brig Gen. Arnold’s Official Report to Sir Henry Clinton, Plum Island, Sept 8th, 1781

- Narrative of George Middleton (1781)

- Narrative of Thomas Hertell, New York (1832)

Powell, Walter L. (2004) Benedict Arnold, Revolutionary War Hero and Traitor.

Footnotes

- Powell, 2004, p. 90-91

- Powell, 2004, p. 92

- Arnold’s Official Report, p. 101

- Narrative of George Middleton, p. 91

- Narrative of Thomas Hertell, p. 73

- Middleton, p. 92

- Arnold’s O.R., p. 100